You Can Do It Too: Inside Scotland's Post-Punk Press with Glenn Gibson

In this post, I chat with a former New Musical Express (NME) writer Glenn Gibson (aka, my da) about his experiences breaking into music journalism in the 1970s-80s, the evolution of music publications, the development of Scotland’s music scene during the punk and post-punk era, and various other bits and pieces.

You’ve got interesting stories about the music industry—I thought it’d be good to capture some of them. How did you get into music writing?

It was the New Musical Express, which was well-established when I started. It’s a music paper dating back to the 50s, and they were credited with originating the UK pop charts. But it was very much tied into the music business. They just had pop stuff and so forth. And at some point, during the early 1970s, they got a new editor who totally revamped it.

Starting in the 60s there was the underground press which was usually independent. And the NME started employing people who wrote for those publications.

So rather than just being a mouthpiece for what was coming out from the big labels, it was able to give space for some more up-and-coming and challenging artists?

Yes, rather than just covering what was in the charts. With the counterculture and all of the post-war developments, music was developing fast.

It went from rock and roll, to the Beatles, and the beat boom, and moved on to prog rock, glam rock, and punk. Around 1976/77 they wanted music publications that would reflect that — written by people who were close to the movement, who were really part of that.

They were probably copying what was happening in America because in the 60s, Rolling Stone magazine started. Rolling Stone is now well-established, I believe it’s quite a corporate thing now. But it started as a counterculture underground thing.

They employed the likes of Hunter S. Thompson for articles?

Yes, some real mavericks. One person they employed was Cameron Crowe, who went on to become a film director. A film he wrote, ‘Almost Famous,’ was semi-autobiographical.

Auch aye, I think we watched that together a few years back.

He was just somebody who was a big music fan. He sent them articles he’d written, and they liked them. I don’t think they found out until later that he was 15. They were sending him off to interview big-time stars and he became really successful. “Almost Famous” is arguably one of the best music business films ever made. I would say that and “24 Hour Party People” (2002).

And Cameron Crowe has actually just published his autobiography, “The Uncool” (2025), because part of “Almost Famous” was that he was never cool.

"That's when I started getting published—and paid."

Anyway, that’s the kind of thing that the NME were trying to copy, and it worked. They got a big audience and it became very cool, internationally as well. It was very well liked in America too. They seemed open to taking on people from around the country, so I went to see Ivor Cutler, the Scottish humorist, singer, songwriter, and poet, and I wrote something about it and sent it to them. They published it.

Oh, crackin’

They came back and said “would you like to do more?” I sent them quite a few things, and they didn’t publish any of them. But then the person in charge of the live review section changed and a new guy came in and he said, “Don’t do that anymore. What you should do is phone me every week and say what’s coming up and we will then commission you to write things.” That’s when I started getting published — and paid.

That being said, I still had a day job as well. Looking back, I don’t know how I managed it.

I guess not having weans helps.

I think the extreme would be working all day and then going to Edinburgh and not getting back home from Edinburgh until five in the morning. And then getting up to go to work. Out constantly at gigs and interviews, and also needing the time to write up.

Aye, I can imagine that took a good chunk of time. Did the acts you were sent to cover align with your tastes, or were you seeing a load of pish? Once they started commissioning, were they picking what you covered, or did you still have a say?

Well, a mixture, because I wasn’t doing exclusively what was happening in Scotland. I was being sent to review other bands who were touring who could be American, but as well as covering what was happening in Scotland because what was happening in Scotland was developing, and gaining national attention.

"One thing punk did was give people the message: 'you can do it too.'"

Starting to develop its own scene?

Yes. Simple Minds were one of the first ones. I went to see them playing in bars. I think they had already signed a contract with a record company at this point, so they were starting to move beyond that, but there were a lot of other ones coming up behind them.

There are probably quite a lot of bands that folk would be surprised to hear came out of the Scottish scene because the accent or dialect doesn’t necessarily come across.

Well, the music business was always very centred in London. This was after punk. One thing punk did was give people the message: “you can do it too.” And what they were playing was relatively simple. That simplicity had origins in early rock and roll. The British beat groups of the 1960s were actually quite ‘punk’ in their way—like The Who, The Animals, and Them. With “Them”, the singer was Van Morrison who is still very successful.

It was fairly simple, thus it’s something that people who were just teaching themselves how to play guitar or bass or drums could play. It was a reaction to progressive rock, which can be very complicated and long and was all about musicianship. That was a backlash against that. The impact of it was quite startling.

I guess there was starting to be more access to recording and distribution equipment during that time?

There were local recording studios, but access to recording didn’t change much during that period. With computers and software it became much easier to record from home, but you couldn’t do that then really, unless you bought quite expensive tape recorders, which could still be quite primitive. So bands would go to record in small Scottish studios. But it could still cost a lot of money. Some of them would be around £600 a day.

Auch, geezo, and I guess that’s £600 then as well.

For people without much money, that was a lot. And the Scottish bands who were playing in bars would be paid very little. I think in some cases they’d get like £10 and there might be four or five people in the band, and they had to hire a van to get there which might cost them about £70 — so they were making a loss. But they were just trying to get their own music out there.

It was an interesting dynamic but that message about “you can do it too” was quite widespread. And more than just music. For instance, my friend Martin Millar was very influenced by that ethos to become a writer. Actors, writers, people across the creative arts—a lot of people were influenced by that, and still are today.

I got to do [the writing] for a number of years and earned a reasonable amount of money and got to travel around and meet a lot of people. And with various different publications, I probably did it for about 11 years. Although you got some money, it was difficult to actually make a living.

Because it was quite sporadic?

Yeah, it was unreliable, I was just a freelance person who was also working a day job. There were some people who did the writing exclusively. However, they were probably getting unemployment benefits and things like that, or there might have been some other small local things that they did. There were a couple of people who went on to write for the local newspapers, doing the pop column.

Which is a bit more of a reliable income.

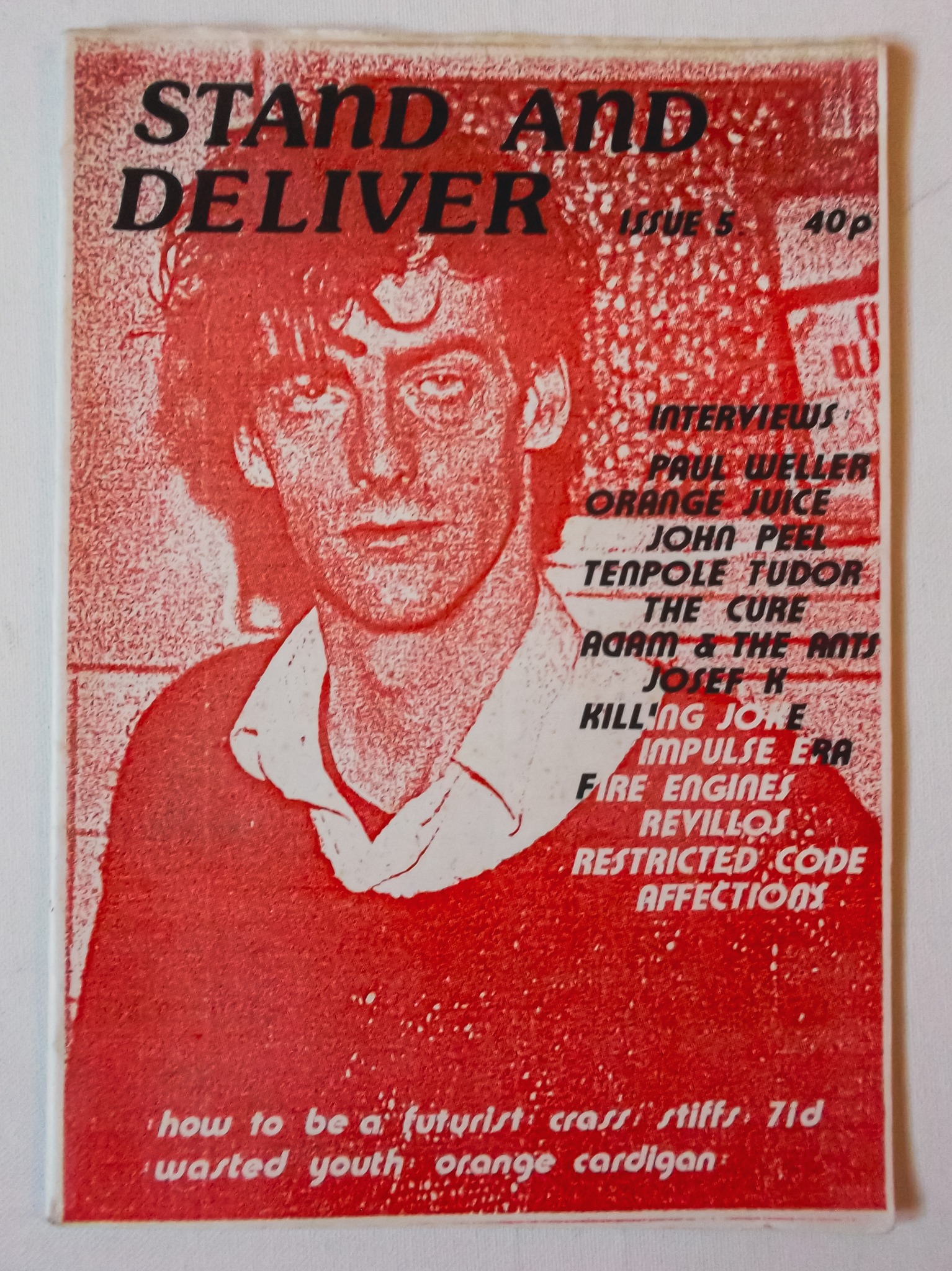

Yes, John Dingwall, for instance, he started off with a fanzine and then wrote for Record Mirror.

When he was just doing Record Mirror he probably wasn’t getting that much, but he went on to work for the Evening Times and Daily Record and he did that for a long time, and has been a core part of Scottish journalism since.

Making money from journalism at that time, even if you were employed by a Scottish newspaper which was predominantly sold in Scotland, you were paid quite well. The circulation of newspapers today has plummeted since then.

Aye, the issues that face the entire journalism industry today is a whole fraught topic unto itself.

I do know some people who moved to London and maybe had a bit of success. But they weren’t getting paid that much just working for music papers, or smaller music magazines, they were very often living in cheap accommodation: squats, somebody’s spare room, or flats with only cold water and broken windows.

I guess in a sense that’s quite punk. You’re getting an appreciation of your source material.

Right, the other side of that, is that the several people I can think of that did that, they all died quite young. In their early 60s and some even younger.

"They'd get like £10 and there might be four or five people in the band, and they had to hire a van which might cost them about £70—so they were making a loss."

Is that what a lifetime of substandard heating will do to ye?

Yeah, and maybe not being able to feed themselves properly as well. It might be a coincidence.

People say the body keeps score.

Yes, I obviously have nothing definite about it but you know, it happened to one photographer I worked with. He moved to London and got a job working for “Sounds” which was quite a good magazine. Quite well regarded. And I think after that, he even got a job working for Marvel.

I used to go and stay with him sometimes in London, but I kind of lost track after a while. Anyway, he got a brain aneurysm. He came back to Scotland a number of years ago and I think he’s in a care home.

The singer from the Bluebells, Ken McCluskey, who we knew, discovered that this guy Harry Papadopoulos was back in Scotland. And the reason Ken found out about it, was because Harry’s brother was an electrician or a tradesman of some kind and went and did a job in his house. The subject must have come up. Ken went to visit him, and they managed to get a hold of his old negatives. They’ve been on display in several art galleries and so forth. And there was a book published.

There was the “Rip It Up: The Story of Scottish Pop” exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland in 2018, where there were a couple of things you contributed.

I never really collected a lot of memorabilia, but there were some things I had. Part of the reason for it is that a lot of people in the past have been asked to lend things of that type and never got them back. So a lot of people who were asked to lend things would say “nah, not doing that”. But with the National Museum of Scotland they were known for being quite reliable, and you did get everything back. So it ended up being quite extensive, and showing off a lot of items never seen before.

Speaking of Scottish pop history being museum-worthy, what place do you think this sort of thing should have in our collective consciousness?

Occasionally in YouGov questionnaires they’ll ask things like “What does Britain do best?” I’m not saying things like industrial products—I’d say music, comedy, acting, writing, and the arts in general. And it’s hard to think of things that Britain does better than those kinds of things.

Aye, a lump of steel is more-or-less the same wherever it’s from. But music, comedy—that’s a product of the people and the culture. You can’t get that anywhere else.

For a very long time pop and rock music that was listened to internationally was almost exclusively from Britain and America. And that has been changing. There were certain countries, like Germany, that became quite successful, or at least critically recognised for what they were doing.

Aye, they weren’t playing Kraftwerk on Clyde One initially.

No. But there were a lot of other things coming out of Germany at that time, but it probably remained quite underground, or a niche interest. That’s continued—music from other countries gaining recognition in the UK. And now that you have K-pop and J-pop, these are massively successful.

Aye, it’s good to see that things are getting a bit more nuanced than just the catch-all term of “World Music”.

Yes, there were phases—African music was a thing for a while, and reggae especially — Jamaica was close to America which may have helped with discovery and distribution. It very much had its own sound, developing over the years from ska to blue beat to reggae, and they had their own version of rap quite early on.

Aye, and you see how dub influenced music worldwide. I’ve been noticing Afro-house having a similar reach lately.

Africa has so many different countries with their own traditions and own styles, but certainly around that time they would have had a lot of influence from what was coming out of Britain and America.

I suppose folk in Britain and America had a lot more access to the mass production and distribution required to get their music heard internationally.

A lot of these things are very popular in their own country and only certain ones break through internationally. There are certainly people that can help give it a boost. Paul Simon recorded an album with African musicians in the “Graceland” album a number of years ago. And he got a lot of criticism because South Africa had apartheid going on and there were supposed to be cultural boycotts.

However, I think his point was more that “this is the cultural bit and we’re actually paying people quite a lot more than the going rate”; and some of them got successful careers out of it internationally.

I wonder how many of those musicians were hitting oot with ‘I love apartheid, now here’s Wonderwall.’ Probably not fans of the regime themselves.

Most of the South African musicians involved were Black artists who had lived under apartheid and whose careers were constrained by it — but I think the boycott of South Africa was for the whole country. Therefore, even if you were working with people who were victims of it, it was still frowned upon in many ways. That being said, I think Paul Simon was quite a tough guy with a lot of self-belief, so he just did it anyway.

This was all well before my time, did it seem like the boycott was a significant part of how the apartheid came to an end?

Probably yes, but there are lots of factors beyond that.

Well, thanks for this chat—there are plenty of other threads we could pull on. The Virgin Megastores opening, people you’ve met over the years. Whenever a random track comes up you seem to have an anecdote ready.

I think for certain things I have quite a good memory. There’s this common thing that for some people, there’s certain types of music that they liked when they were in their late teens and that’s what they like forever. Whereas I’ve always wanted to find new things; and there are some people like that, but I think that’s the minority because you have to put some effort into it, and you do have to be interested. And if you’re interested enough you will remember these things.

I think to this day you’re my main source of interesting new music. I find stuff on my own, but it’s more through happenstance than actively seeking it out.

I think if you’re interested in music quite a lot, it ties in with so many other things. That would lead you into particular types of books or films or art. It’s all tied together.

Cheers da!