DNN64: An ML Compiler Toolchain for the Nintendo 64 (Part 1)

In the first of a series of blogposts, I discuss my experience developing and accelerating a compiler toolchain for running deep neural networks on the Nintendo 64 (1996). I endeavoured to use modern tools (e.g., Apache TVM), and acceleration techniques which are relevant to today’s models and hardware accelerators. But of course there will be special considerations required to fit them to the unique hardware and software environment of this beloved (by some, it was out before I was born) games console. This first post will give an overview of my system design, and future posts will go deeper into individual challenges (in ML, compilers, and hardware).

I’m interested in tensor compilers, especially those for deep neural networks (DNNs). One attractive feature of many of them, compared to hand-written kernel libraries such as cuBLAS, is that you can take a given program as input and generate code for multiple different hardware and software backends.

At the start of my PhD, I got more familiar with the Apache TVM tensor compiler, and it was what helped solidify my belief (and one of the key takeaways of my PhD thesis) that domain specific compilers will increasingly be the centre of the deep learning systems stack. You can read a bit more about that stack in my overview paper: “DLAS: An Exploration and Assessment of the Deep Learning Acceleration Stack”, as well as in my thesis.

One thing I’ve wondered for a couple of years is how easy it would be to get a modern DNN working on retro hardware, especially games consoles. Some like to market DNNs as the hot new thing, but they’re an old idea, its just recently that the availability of large datasets and powerful hardware has made them more practical and scalable. The training of these networks is the most compute intensive part, with inference (i.e., deploying a trained model) being relatively cheap — though still important to optimise when running at scale. Could we run a pre-trained DNN on, for example, a machine older than me?

Hence, this project was born: DNN64, where I try and run (and hopefully accelerate!) DNNs on the Nintendo 64 games console. I don’t yet have access to real N64 hardware, but luckily there is a dedicated community of folk who develop emulators for it, such as ares, cen64, dgb-n64, simple64. There’s even an FPGA emulator pretty far in development! Kudos to them, as it serves an important public good of ensuring that the cultural artefacts of these games will still be archived and usable long after the last N64 has broken down. My initial development will be in these emulators, and if any of my pals have a real N64 in their attic somewhere, I’d love to try and run there too.

I’m going to structure this first post introducing the core components of my solution (the N64 toolchain, the N64 hardware, Apache TVM, and how we bring it all together), as well as the challenges we face regarding acceleration. Future posts will discuss how those challenges are tackled, as well as my efforts towards optimisation. For the record, I have no experience with game console emulation and retro homebrew development — I came at these topics as an outsider. Please get in touch if you spot any errors!

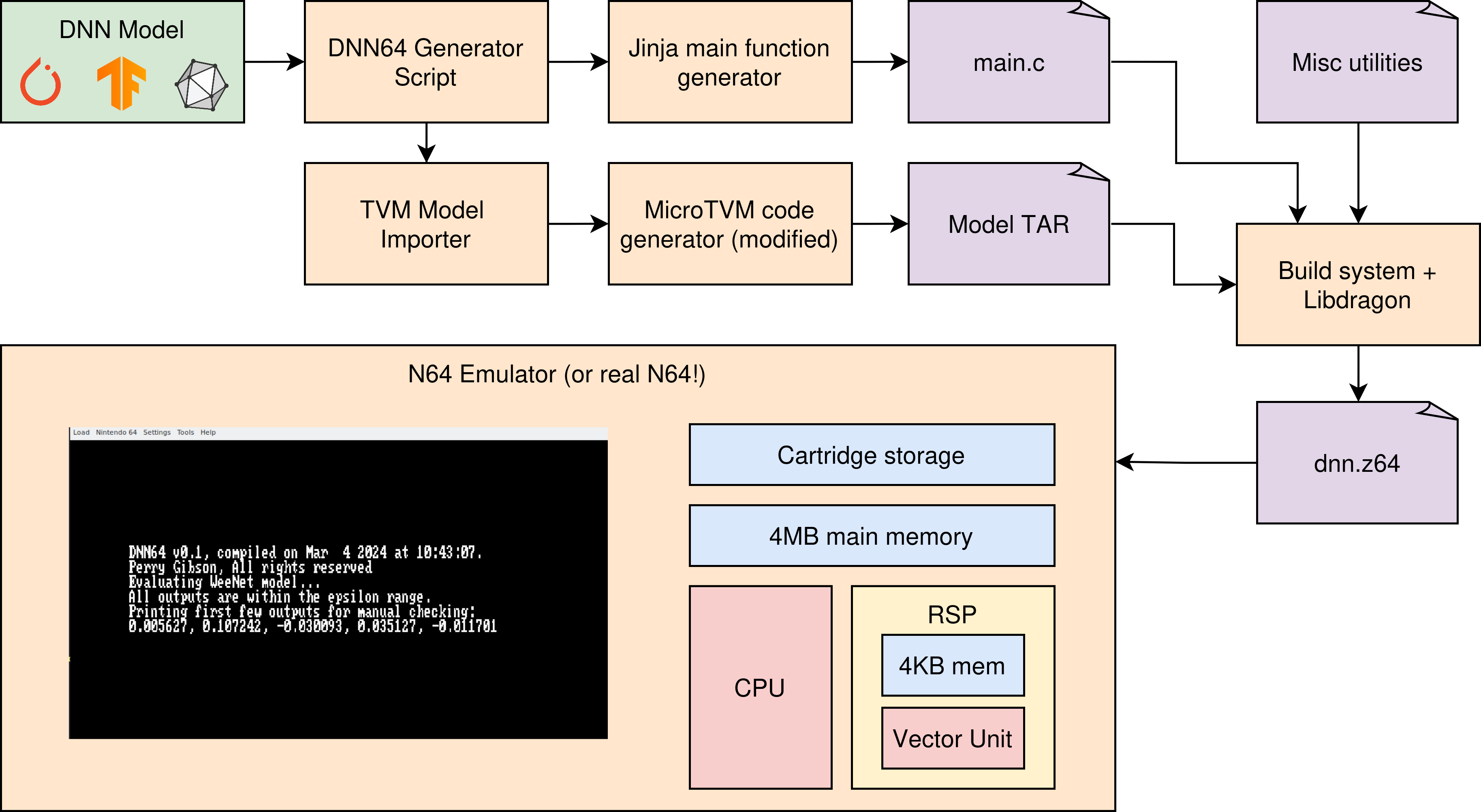

At a high level, you can see a sketch of my system in the below figure. I hope that this series of posts will help make clear the relevant components, how I desgined and implelemented them, and my strategies for optimisation.

The N64 toolchain

Back in the 1990s, folk typically programmed for the N64 in assembly and C.

Nintendo sold an official development kit called Ultra64, and some folk still develop using that (both legal and pirated copies).

As an aside, I recall hearing that Super Mario 64 was one of the first titles that Nintendo developed using C, and for the original Japanese release, reverse engineers have discovered that they didn’t enable compiler optimizations (i.e., with -o2 or higher).

It’s a testament to their rigour that it runs as well as it does, except for a couple of corners exploited by speedrunners.

We have two main options for our project: either we program in C and use an existing N64 compiler toolchain, or we get another toolchain (say TVM) to generate code for the N64’s ISA directly. I’ve gone for the C approach, but don’t despair compiler heads, I’ll be using a compiler to generate C! The reason for this is that there will be a lot of hardware knowledge represented in the configuration on an existing N64 compiler toolchain — I don’t relish the thought of trying to reproduce it all in LLVM, and be ABI compliant if I want to integrate with other tools such as those for showing graphics.

First, I tried compiling a modern version of gcc to generate code for the N64’s MIPS CPU architecture (discussed more in the next section).

This was going off of this WikiBooks page on N64 development

See my post on other gcc build issues you might encounter if you go down this route.

However, the next steps of creating an N64 ROM cartridge (typically distributed as .z64 files) from my binary had a few too many steps.

Given that is was getting cumbersome, I looked further afield for a more specialised toolchain, ideally with an active community.

Next, I found a pre-configured N64 toolchain n64chain, which seemed to provide some of this functionality. It seemed great, however it was missing one critical piece of code required — the boot code, for booting up the system. This is copyrighted, and not distributed by the authors of n64chain for obvious reasons.

Fortunately, it appears that folk have been able to make open source versions of the boot code, and also exploit hash collisions in the N64’s checksum to allow it to be accepted by the console. More details of that are given here.

My adventure into finding a legal and functional boot code let me to the libdragon SDK, which includes open source boot code, as well as a lot of other quality-of-life tooling for N64 development. Therefore, I opted to use this for the DNN64 project, and I’ve not looked back.

Libdragon builds off of a modern version of gcc, but provides N64-appropriate build configurations to make it easier to generate that coveted .z64 file which actually works.

It makes it straightforward to include C standard library functions, and provides its own utilities for things such as 2D graphics programming (with a port of OpenGL for 3D graphics under development!), debugging, audio, and data management.

I’ll be packing up my full workflow for DNN64 at a later date, but if you’re interested in getting started with libdragon, I would recommend the containerised CLI, at least for your initial steps.

The N64 hardware

Now that we can compile basic C programs for the N64, what hardware are we working with, and how does that limit or potentially enable DNN inference? We can go into greater detail as required during this post series, but let’s get a high level overview. My major source for this information is this excellent summary by Rodrigo Copetti, as well as the N64brew Wiki.

First things first, as you’d imagine, the 64 in N64 comes from the main processor, the NEC VR4300, which has wide enough buses, registers, and compute units to support 64 bit computation. The CPU was developed by Silicon Graphics for Nintendo, using the MIPS III ISA. CS students, you may mind the Patterson and Hennessey computer architecture book. Well Hennessey was Chief Architect at Silicon Graphics, and the examples in the book (at least the version I have) are in MIPS. All you really need to know is that it’s a reduced instruction set computer (RISC) ISA, examples of which include the ARM architecture and the new open-source RISC-V.

The N64 has a unified-memory architecture (UMA) with 4MB of RAM (extensible up to 8MB with an expansion pack). This memory limit is going to be our main challenge for deploying DNNs: even modestly sized DNNs can have dozens of MBs of parameters, not to mention their activations. We’ll discuss that more in a future post.

This is originally a games console, so graphics gets a dedicated system, called the “Reality Co-Processor”. Although the architecture is pretty different from modern graphics cards, we could call this the GPU. We often accelerate DNNs on GPUs, so is there anything in the N64’s Reality Co-Processor which could help us achieve that goal?

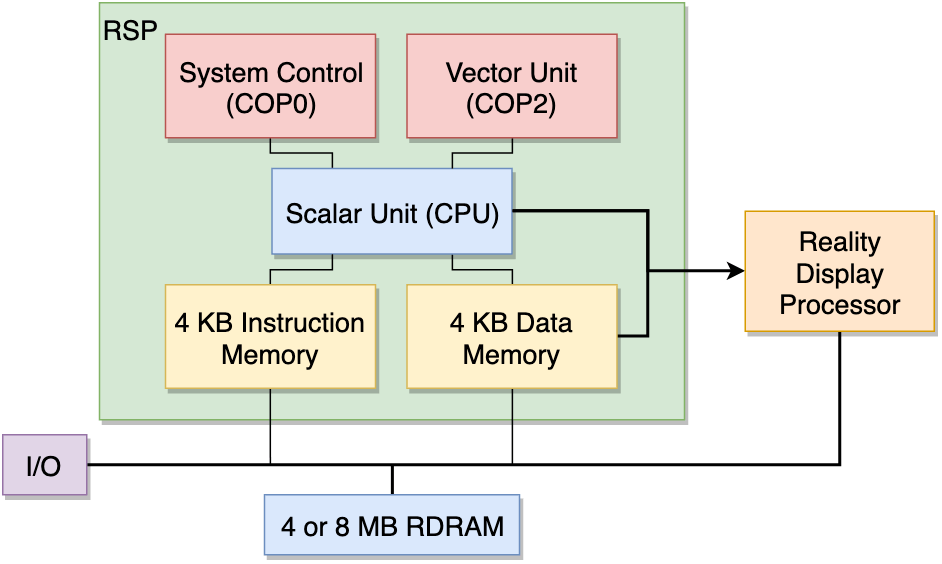

I think there is: a sub-component called the Reality Signal Processor (RSP), with the architecture shown in the figure below, courtesy of Rodrigo Copetti. The RSP is essentially another CPU package, with a scalar unit, which I believe is the manager of the RSP, and Vector Unit which is does the bulk of the compute. The vector unit does operations with 32 128-bit registers, where each register is sliced into eight parts to process eight 16-bit vectors at once. If used correctly for our DNNs, we could potentially get some pretty high speedups thanks to the parallelism that SIMD unit provides.

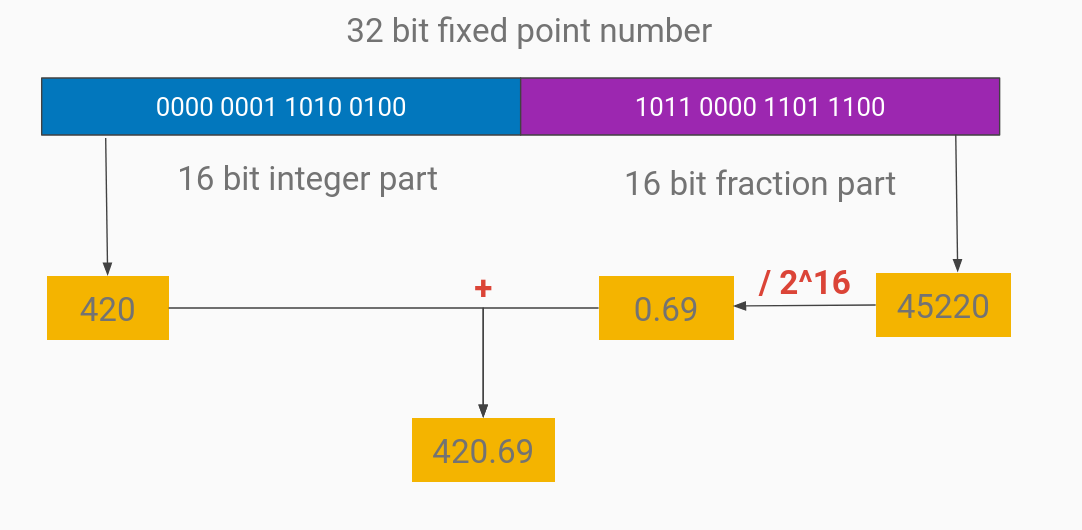

The main CPU of the N64 has a floating point unit (FPU), but we don’t have floating point number support in the RSP’s vector unit.

That means if we want to approximate the float numbers typically used in DNNs, we’ll need to use fixed point numbers.

In this case, that would be 16 bits for the integer part, and 16 bits for the fractional part.

An example of that is shown in the figure below.

That might not be ideal for DNNs, where most of our values are between 0 and 1 anyway.

This is what motivated the creation of the bfloat16 data-type.

Alternatively, we could look at quantizing our DNNs to use integers, but we can leave that for another post.

Additionally, the RSP has 4KB of instruction cache, and 4KB of data cache. So if we want to use this to accelerate our DNNs, we need to think carefully about how and when we copy data to and from the RSP. We’ll look into this issue in a future post - for now it will be okay to run our DNN using the main CPU of the N64. If you’re interested in the topic of data movement to-and-from DNN accelerators, I’d recommend the AXI4MLIR paper, which I co-authored.

When developing this project, I’ll be using an emulator, which is a software program that emulates the hardware of the N64 on another machine, e.g., my laptop. Ideally there should be no difference between the real hardware and the emulator, but there are always some differences. For now, it is sufficient for development, but I’ll need to test on real hardware before I can say that I’ve succeeded in my project.

Apache TVM

Now we have some more information about the hardware we’re deploying to, we can think about how we can get our DNNs running on it. I mentioned Apache TVM earlier, which is a tensor compiler which can take DNN models from a variety of sources (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow, ONNX), and generate efficient code for a range of platforms, including Arm, Intel, and RISC-V CPUs; Arm, AMD, and NVidia GPUs; OpenCL, CUDA, LLVM, and Vulkan software backends; and more. I’ll discuss more of how TVM works as required in this post series, but check out its excellent docs and tutorials if you’re interested in learning more.

The question is how can we use TVM to generate our code for the N64? We could export to LLVM, and then go to our MIPS backend from there. But since C is a bit more hackable for a single person, and we have a C toolchain already to go, why not do that? Fortunately, TVM has a backend for that too: MicroTVM. Originally intended for deployment in microcontrollers, MicroTVM can generate C code, which can then be deployed using whatever a given microcontroller requires. It generates C, with the rationale that almost everything has at least a C compiler.

This tutorial is the most pertinent to our deployment requirements, since it generates C code directly, rather than trying to integrate with a known toolchain. If we untar the file it genrates, we should have all of the code we need to execute our model, including the model definition, weights, and runtime. We will need to tweak the code generation a bit later, but for now this has taken us a long way.

Note that I also considered the Darknet framework, a DNN framework written in C. But since it isn’t a compiler, it means we would include a lot of unused functions if our DNN doesn’t use every single layer type it supports, and we lose a lot of potential optimizations (e.g., loop unrolling) by not knowing our shapes ahead-of-time.

The combination of libdragon and TVM

Two things we need are integration of our TVM model code with our libdragon build system, and a way to automatically generate our inference management code (i.e., our main function).

The generated TVM code should be relatively self-contained, though still requires some standard library functions.

My go-to for these kind of projects is usually CMake, but I elected to stick to a Makefile, since libdragon already provided a pretty decent build config for our target backend, and I didn’t want to try porting it over. There isn’t much more to say about the build system: anyone that’s had to wrangle a build system for a new project will tell you it can be annoying, and once the core is set up, don’t poke it too much. It works, and that’s what matters.

For our main function, we need to be able to:

- Load some sample data for our target model

- Load and execute our target model with the sample data

- Fetch the output, and compare it against our target output

- Print any info or debug messages that will help us understand the execution

We could hardcode this for every model that we want to deploy, but that’s not very compiler-brained — our programs should write themselves.

The approach I’ve gone for is to use the Jinja templating engine, typically used for generating HTML files, in frameworks such as Flask, I’m using it for C, defining a main.c.template file for our project, which we populate as required.

By using the double brace syntax {{my_var}}, we can define substitutions that can be placed in our code by the templating engine.

Sidenote: multiple braces can be valid C syntax, which could cause us problems. So far, my template doesn’t have any, so the point is moot, but another syntax might be better for larger systems).

We could have a template like:

#include <libdragon.h>

#include "tvm/runtime/crt/platform.h"

#include "tvmgen_default.h"

#include <math.h>

{{samples_import}}

int main(void) {

{{target_outputs}}

{{output_dtype}} actual_output;

{{output_dtype}} expected_outputs[{{num_outputs_to_check}}];

inputs.{{input_name}} = (void *)&{{sample_name0}};

// rest of the code

}

We can then use Jinja to fill in these fields with ones relevant to our target model.

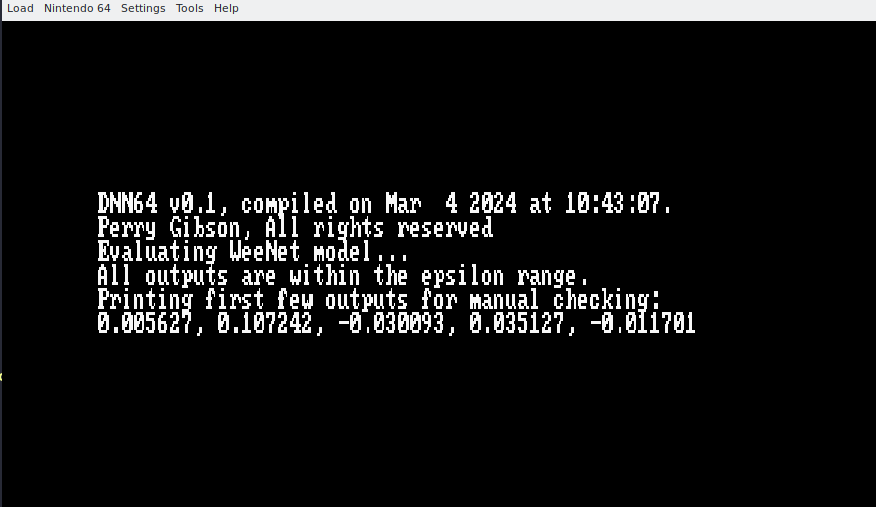

With our build system and main function ready, we can compile our a small test model, and execute it on an N64 emulator. Here it is!

Conclusions and acceleration challenges

This post briefly introduces the workflow I’m using for DNN64. With just a bit of elbow grease, we can get DNNs running on the N64! But there’s still work to do. We are especially limited by the 4MB memory of the N64, so there are lots of optimizations we’ll need to apply to get non-trivial models working. This includes changes to our code generation, quantisation, and understanding how the graphics accelerator of the N64 can be exploited. We’ll talk about those in future posts, as well as going deeper into my code which I will be open sourcing. For now, catch ye.