AI Generated Music Video: SENGA 'Bloodshot'

I recently had the opportunity to help produce a music video for the upcoming album from SENGA AKA Sean Cosgrove.

You can read about the track, and the album in this piece in DJ Mag.

The video is AI generated, and I thought I’d take this opportunity to give a brief overview of how I put it together.

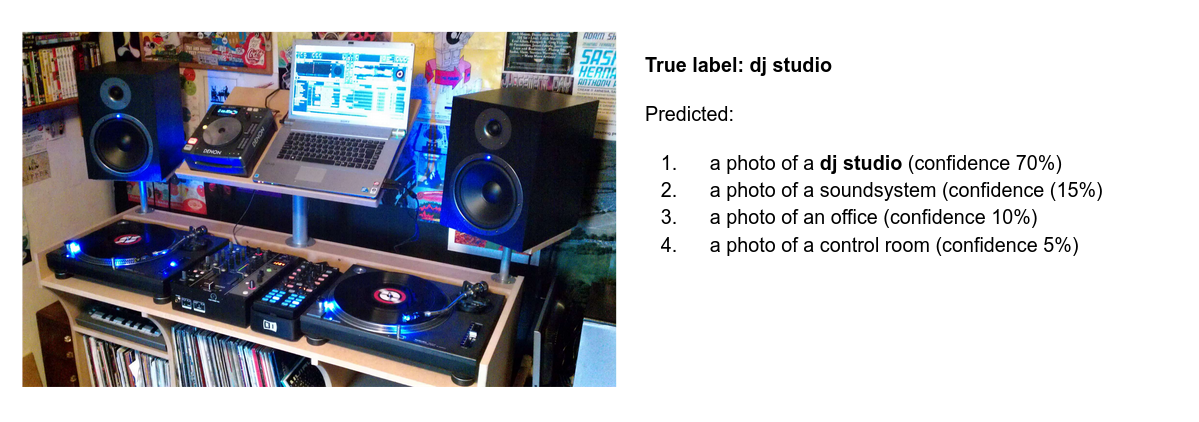

Recent months have seen an explosion of AI generated visual art. This has been enabled by a couple of key innovations. Firstly, the introduction of OpenAI’s CLIP model, which is trained to generate captions from images. It learns this by being showing millions of images with text captions, and being trained to predict the captions from just the image. An example of this kind of dataset is Google’s Conceptual Captions.

Secondly, was the public release of the BigSleep and LatentVisions systems by @Advadnoun, and the subsequent iterations from the artistic machine learning community. The contribution of this work was to take neural network models which can generate images (such as GANs [basics], [state-of-the-art]), and connect them to the OpenAI clip model.

In practical terms, this meant:

- specifying a text prompt of what you wanted to be generated (e.g. a pineapple wearing sunglasses)

- using the image generation model (let’s call it G) to generate some random noise

- Get CLIP to look at the generated image, and give it a caption

- Measure the distance between the caption, and the desired text

- Give feedback to G on how it could nudge its parameters to generate an image closer to the prompt

- Generate a new image, and repeat steps 3-6 until you’re happy with the results

In May 2021, I came across the notebook versions of BigSleep and LatentVisions, and wondered what would happen if one changed the prompt midway through, and collected all of the generated images together into a video. I made a proof-of-concept, which I discussed and demonstrated in this Twitter thread.

As demonstrated in the above video, I started with the prompt “a city during the day”, the changed the prompt to “a city at night”, and finally “a city on fire”. The model training takes the path of least resistance, and thus we see some continuity between the images. I also added some code that messed around with learning rate decay, but this is outside of the scope of this casual blog.

Next, I wanted more fine-grained control of the generated video. Thus, I devised a system where the user could define how long they wanted a given prompt to be generated for. I decided to use the LRC file format, which is a simple plain-text file format used for setting the lyrics of a song. You need only prefix each line with the timestamp it begins, for example:

[00:12.00]Line 1 lyrics

[00:17.20]Line 2 lyrics

[00:21.10]Line 3 lyrics

...

[mm:ss.xx]last lyrics line

I built a parser for this file format, and connected it to my prompt changing code. I made a bunch of music videos using the lyrics to various songs, which I can’t show you for copyright reasons.

Since then, a large community has grown around CLIP driven image generation, with an almost “zine-like” culture of people cutting and pasting code, and mixing stuff together, collaborating and sharing. My other work as a PhD student has precluded me from getting more involved, but I encourage you to check out what they’re doing, out there in the disparate wilds of Online.

I was very pleased when Sean reached out to me about making a music video for the track in his new album. We had a discussion about the direction I see the tech going, with DJs being able to easily mixing both visual and audio elements in real-time, enabled by AI systems such as this. That’s not to mention areas such as automatically making short films from books, and other modes of artistic expression that are still nascent. We were also realistic about what the tech can do right now, and my own limited resources. There’s very little in the way of lyrics for the song, so instead Sean put together descriptive text, that reflected the themes of the song, and those of the wider album.

In future, I’d like to have the system more directly exposed to the underlying music, and be more free to make its own interpretations. A naive version of this system I envision would hook in an FFT of the music, and use that to adjust the learning rate following the beats of the music. A more nuanced approach would require a larger dataset, perhaps of music and lyrics, or music and music videos, so that the system can learn a mapping between sound and imagery.

You can see the final video for SENGA “Bloodshot” below: